|

|

2020 DELMARVA Reports |

Home

|

I boarded our sailing vessel NAVIGATOR on

Sunday, October 4, 2020 while she lay at dock at Lankford Bay Marina, Rock Hall,

MD. This allowed me a few days to inspect and prep the boat and lay in food

provisions for the forthcoming DELMARVA circumnavigation cruise before Captain

Jerry Nigro, my Mate for this cruise, was due to arrive on Thursday. During a

previous cruise in July, NAVIGATOR was struck by lightening, which

blew out all of her electronics and much of her electrical equipment and wiring,

and she underwent a two-month repair period at Haven Harbour Marina where all

the damage was repaired. Immediately upon completion of this work, NAVIGATOR

completed two DELMARVA circumnavigation cruises in September, one with Captain

Steve Runals and the other with Captain Frank Mummert. Thus, early October was

my first opportunity to spend some time onboard and become familiar with the

newly installed equipment, which I did with pleasure since everything seemed to

work perfectly... a good omen for the forthcoming cruise. Jerry arrived on Thursday as planned and proceeded

to refamiliarize himself with the boat, on which he has sailed several offshore

cruises, and the newly installed equipment. Jerry and I have sailed together on

many ocean cruises over the past 20 years, on my boats as well as his. Jerry

owns a Skye 51 foot cutter rig on which he completed an Atlantic Circle cruise

New York-Bermuda-Azores-Portugal-Madeira-St Thomas-Florida-Bermuda-New York in

2015. I sailed several of these legs with Jerry, and the last two legs also

included MDSchool students. Two weeks prior, we held an online meeting with all

crewmembers for this DMVA cruise plus Rita who gave a run down on administrative

matters and Covid procedures. Student sailors in attendance were: Michael Acker,

Johan Liljeros and JP Sarmiento; we usually carry four students for this cruise,

but in deference to the Covid, we limited it to to three students. I then

reviewed our plans for the cruise including the itinerary per the DMVA Training

Plan, cruise route per the charts, pre-cruise assignments, preparation

guidelines, mainsail single line reefing diagram, and the meal plan. The DMVA

cruise involves a great deal of meticulous coastal navigation in a variety of

conditions and venues. To help prepare for this, I made the following

assignments to be completed prior to the cruise:

·

JP- Lookup current forecasts for the C&D

Canal, Delaware River at Reedy Point and the Cape Charles Bridge; identify any

Dredges operating along our route. · All- Review the Training Plan provided including all videos listed there plus the new video Navigation Preparations for an Advanced Coastal Cruise

Then, on Friday afternoon October 9th, our three

student sailors arrived onboard, stowed their personal gear and we proceeded to

inspect NAVIGATOR below deck from bow to stern including all

stowage areas plus the electronics, emergency gear, galley, engine, tools, spare

parts, logbook setup and charts. After this we went to Harbour Shack Restaurant

for dinner and a relaxed evening where we could tell sea stories and get to know

each other. Our three students had earlier decided to sleep ashore at hotels

during the preparation phase of this cruise to ensure a good night's sleep in

advance of the cruise, and Jerry and I returned to NAVIGATOR. On Saturday we conducted onboard in-port training

per the DMVA Training Plan, a 168 page document, that we wrote to describe the

important actions and procedures needed to complete this 450 mile cruise around

the DELMARVA Peninsula; quoting from the Introduction to this book: Team building is the clear

and over-arching focus of this training, as the smooth functioning of a vessel's

crew as a team is essential to the safe and happy completion of an advanced

coastal cruise in daylight and nighttime operations in all sorts of weather

conditions. Specific activities are

listed and detailed, which student crew need to learn and carryout under actual

operating conditions. Many of the specifics given below are based on the

configurations as currently exist on S/V NAVIGATOR, IP40. As you sail on

other boats with different equipment configurations, you will of course need to

make adjustments in some of these procedures. Following the checklists of the Training Plan, we inspected

all deck equipment and rigging, raised and reefed all sails, rigged the main

boom preventer line, deployed the whisker pole, practiced engine starting and

stopping procedures, tried on the Type I PFDs, coiled and tossed docklines and

throw rope, deployed the MOB horseshoe and pole, noted the locations of all five

onboard fire extinguishers, reviewed the cockpit electronics, and completed the

remaining items in the checklists. I then assigned crewmembers to complete the

specific checklists for Navigator, Bos'n, Engineer and Emergency Coordinator and

followed that with a review of weather and preparation of our underway

navigation plan for the next day's transit to Swan Creek for an overnight

anchorage. At this point on Saturday, the weather forecast looked a bit

challenging for Monday, the day we plan to proceed north up Chesapeake Bay, with

expected winds of 20 to 30 knots from the north... right on our nose! On Sunday, the weather dawned clear and calm, but the forecast for tomorrow remained 20 to 30 knots from the north, so we made a last minute change in plans to proceed from our Lankford Bay Marina in Rock Hall directly to the C&D Canal about 50 miles to the north up Chesapeake Bay with no stops along the way. Crew went through the "Day of Departure" checklist in the Training Plan and we were underway at 0840 for the ten hour trek to the C&D Canal. Yesterday we had prepared our navigation plan only for the cruise leg to Swan Creek, so Johan and JP worked on the additional navigation planning needed to reach the Canal while Mike and Jerry stood watch underway until the additional nav prep was completed. There was very little wind movement this day, so we motored all the way to the Canal reaching the Summit North Marina at 1800 hours where we docked on a T-head floating dock, secured the boat and went to the Grain Restaurant for dinner and showers. Then lights out by 10:00 pm with the plan to remain in port tomorrow while the forecast storm passes.

By Monday morning the storm clouds had in fact

gathered and gale-force winds were beginning to howl, so after breakfast we

moved to the fuel dock to top up our diesel tank and pumpout the waste holding

tank and returned to our T-head dock. This will be a down day in port that we

will make good use of by preparing the navigation plan from here on the C&D

Canal, down Delaware Bay, south along the Atlantic Coast of Delaware, Maryland

and Virginia to the entrance of Chesapeake Bay at Cape Charles, and north up

Chesapeake Bay for several miles to Cape Charles Town where we plan to

overnight. The crew got busy with this sizeable task following the guidance

provided in the Training Plan and our recently published YouTube video titled: Navigation

Preparations for an Advanced Coastal Cruise. The crew worked as a team, all participating in the

activity, so that everyone knew the details of the route to be sailed,

waypoints, course directions and distances, Light List and Notices to Mariners

references, and the electronic course plotter as well as the paper charts. After

this the student crew wrote their ASA106 exam, which I reviewed and

graded after the cruise. By this time it was late afternoon, and we all again

went to the Grain Restaurant for an early dinner as we plan to be up and

underway bright and early tomorrow morning. By Tuesday morning the weather had moderated and

mostly cleared as we exited the marina at 0700, entered the Canal and turned

left, eastward and passed under the Conrail bridge, which was in the up position

so there was no need to contact the bridge tender. Sailing is not permitted in

the C&D Canal, so we set the engine speed to 2400 rpm and moved along

briskly down the flat waters of the canal. We knew that the Delaware River

current at Reedy Point, where we would exit the canal into river, was ebbing and

thus flowing outbound toward our right. We would thus be making a full turn to

starboard as we entered the strong current of the river and needed to make this

turn at the appropriate spot to ensure that we avoided the rock jetty extending

out from the canal on our starboard side. We accomplished this by pre-planning

our turn to be made when abeam of the red over green buoy (RG "CD"

Fl(2+1) R 6s) to our port side. Since we were on a course of 092ºC in the

canal, we verified this turning point when the buoy bore 002ºC on our port side

and double checked this with visual confirmation that we had in fact passed the

end of the jetty. We then turned SE to a course of 152ºC toward the green

buoy (G"11" QG) of the main ship channel. As we proceed down the

river, our plan is to remain on the west side of the main channel leaving the

green NavAids close aboard to our port side. We generally think of Delaware Bay

as a "nasty bay" with lots of shoaling, strong currents, fast-moving

big ships and lots of other traffic. So we need to pay close attention to our

navigation and watch keeping, and we set the watches as follows:

Current in Delaware Bay and River varies between two knots

Flood and two knots Ebb and can thus have a significant impact on transit times

down the Bay. Of course, traveling at a 6 knot water speed over a distance of 60

miles will expose us to both max Flood and max Ebb currents, but it would be

helpful to have more Ebb than Flood when traveling south from the C&D Canal

to Cape Henlopen. The NOAA Current Tables include a simple graph to help

mariners estimate the optimum time to make this passage on any given day.

Notice the lefthand column of geographic names starting

from Delaware Bay Entrance at zero miles at the bottom and Bristol at 100+ miles

at the top. Across the bottom is a series of time legends correlated to times in

the current cycle starting with "Hours before Flood Begins at Delaware Bay

Entrance" on the lefthand side. On this legend the current would be Slack

at Delaware Bay Entrance at zero hours before Flood begins. The main body of

this graph shows Flood and Ebb areas correlated with these time and geographic

names. Proper setup of this graph for our date and time of entering the bay will

allow us to estimate the currents to be expected during our transit down the

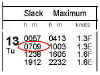

bay. On this date of Tuesday, October 13, 2020 we passed Reedy

Island at 0900 EDT or 0800 EST. The NOAA Current Tables for this date show that

Slack before Flood at Delaware Bay Entrance occurred at 0709 EST, so we passed

Reedy Island about one hour after Flood began at Delaware Bay Entrance.

Our boat speed through the water was 5.5 knots heading south. We can plot a speed line on the previous graph starting at Reedy Island at one hour after Flood began at Delaware Bay Entrance, and from there draw a 5.5 knot Speed Line as shown in red in the graph as above. This shows that we can expect Ebb current between Reedy Island and Arnold Point. Current then turns to Flood, or opposed to us, until we pass Fourteen Foot Bank Light where it Ebbs for the remainder of the distance to Delaware Bay Entrance. Tuesday at 1040: Motor sailing down Liston Range

with mainsail on a broad reach in 10 to 12 knot wind from NW; skies overcast

with stratocumulus clouds; waves two feet or less; approaching Ship John Shoal

Light. At 1230 we saw the Racon signal of Miah Maul Shoal Light on our radar

screen flashing Dash-Dash. A Racon is an electronic device that responds to our

radar signal and paints a Morse Code sequence on our radar screen for positive

identification. Chart #12304 shows this Racon and its Morse Code sequence (- -)

as below:

At 1400 we passed Brandywine Shoal Light; skies clouded

over; cooler as late afternoon approaches; current slack as expected from our

previous analysis; speed through water 5.5 knots; speed over ground 5.5 knots.

At 1500 passed Brown Shoal Light. Reefed mainsail one tuck

in preparation for forecast wind increase overnight; expecting NW 15 to 20 knots

with gusts to 25 knots. Unfurled full genoa; secured engine. Sailing 5.5 knots

through the water; speed over ground 5.5 knots. Brown Shoal Light marks the

southern end of the Delaware Bay Main Channel. From here the deep water widens

out to the mouth of the bay, and we set a course for Cape Henlopen requiring a

20 degree course change to starboard and improving our apparent wind angle

enough to permit full sail on a broad reach starboard tack. At 1640 we passed

the green G "5" Fl G 2.5s buoy, leaving it to starboard, which marks

the western corner of the Pilot Area where ship pilots meet incoming and

departing ships. We steered clear of the Pilot area leaving it to our port side

as we proceeded south between the coast and the outbound traffic lane where

outbound ships are making fast for sea usually at 18 to 20 knots.

At 1700, after rounding Cape Henlopen on starboard tack and

turning to a course of 180º per compass to remain between the traffic lanes and

the coastline, the winds became dead astern making for poor sailing conditions,

and we doused the genoa and started engine. Eventhough winds remained at NNW 20

knots, we were unable to effectively sail on this course as we were trapped

between the traffic lanes and the coastline with decreasing depths thus

preventing us from heading up to improve apparent wind angle. So we motor sailed

on while Johan prepared a delicious dinner of pasta and meatballs with fresh

green peppers as a side. By 1900 a cold front passed our location, skies cleared,

stars came out, winds backed to WNW and we were able to unfurl the genoa and

secure the engine for a beautiful nighttime sail on a course of 200ºC in 20 to

25 knot winds, gusting to 30 knots. It was fascinating to actually see

this cold front come through from the west. Initially, skies were completely

clouded over. Then we saw a slight crack of bright sky to the western horizon

where the sun was setting over the land. This crack grew in height over the next

hour and eventually spread overhead and moved to our east leaving a pitch black

sky with billions of stars and a cooling WNW breeze that freed up our sails for

better speed and control. By 2300 we reached the intermediate red sea buoy R

"6" Fl R 6s off of Chincoteague where we changed course to 220ºC to

follow the coastline which is now bending away to the west thus bringing the

apparent wind forward and again improving sailing performance. Beautiful sailing

conditions with clear skies, bright stars, brisk cool air and a very nice boat

motion!

By 0200 on Wednesday morning, with consistent NW 25

knot winds gusting to 30 knots, we reduced the genoa to one-third keeping the

mainsail with one reef tuck. At 0300 crescent moon rising in the eastern sky. At

0500 wind clocked to North at 25 knots. At 0700 Sun up; winds down to 15 to 20

knots NNE; increased genoa to three-quarters out. Sparkling, clear day. At 0715

engine turned on for battery charging for one hour. Solar panel producing 7.0

amps on this bright, sunny morning.

Winds dropped to 12 to 15 knots NNE; bright clear day;

deployed full mainsail and genoa. At 1200 passed the red sea buoy R

"14" Fl R 2.5s east of Cape Charles; sailing 5.0 knots water speed.

Changed course to 246ºC toward the R "2N" Fl R 4s buoy at the

northern entrance to Chesapeake Bay. At 1300 wind dropped to 5 knots; furled genoa; strapped

mainsail in tight; started engine at 2400 rpm on a course to R "2N"

buoy 9 miles distant, which we passed at 1430 turning NW up the Nautilus Shoal

Channel toward the bridge span and passing through the bridge at 1600. We then

set a course 356ºC for Cape Charles about ten miles distant. Weather forecast for today, tonight and tomorrow is

favorable for the trip up the bay to Annapolis, but by Friday the forecast is

for 20 knot winds from the North plus rain and limited visibility, not good or

an overnight cruise up Chesapeake Bay with the normally many commercial ships

underway. Johan suggested that, in view of the weather forecast for the next two

days, we consider continuing non-stop direct to Annapolis. Mike readily agreed,

and it sounded like a good plan to me, so it was agreed that we would continue

on north now, and decide at the time whether to go into Annapolis or continue

straight through to home port at Lankford Bay Marina. JP and Johan developed the

navigation plan for the remainder of the cruise up the bay to Rock Hall. At this point, I changed the watch schedule, switching JR

and Mike, all else remaining the same, as follows:

The overnight passage up the bay went well with pleasant,

cool weather; clear skies, winds building to 15 to 20 knots from the south which

was just great for our trip north. We kept the mainsail single reefed and used

the genoa variously as the wind angle permitted. Met a number of ships

overnight, traveling both north and south, but these were handled well by the

watchkeepers who were now experienced with night sailing and use of the radar,

AIS, VHF radio, charts and their eyes for spotting ships as well as buoys and

potential obstructions. By Thursday morning, we decided to skip Annapolis and go directly to Rock Hall today in view of the expected adverse weather for Friday. Passing under the Annapolis Bay Bridge, we turned NE toward Love Point at the north end of Kent Island bringing the apparent wind forward to a good broad-reaching angle on starboard tack, and NAVIGATOR charged ahead with renewed energy. Approaching Love Point we turned further east to begin rounding Love Point marker on an exhilarating beam reach. The crew clicked perfectly, as a well-oiled team, expertly doing their assigned duties as helmsman, line handlers, lookout and navigator to thread between the many fishing boats and passing yachts while achieving quality sail trim and maximum boat speed. Passing Love Point rocks, we headed up further on the wind to close-hauled and roared ahead at eight knots. It took a few tacks, well executed, to reach the horseshoe river bend where we bore away to the east for a mile then gybed, executing a perfect PST-TSP gybe per the Training Plan, and headed north toward Langford Creek and home.

Once past the R "14" red buoy, we paused to

conduct some MOB drills using Weenie, our MOB manikin as the overboard victim. I

threw Weenie overboard, and, with each student taking a turn at the helm, we did

a quick stop tack and back, furled the genoa, dropped the mainsail and motored

close to the victim for a pickup with the boat hook. This illustrated the

principles of quickly stopping and using engine power for maneuvering for the

pickup. All went pretty smoothly. Speed

Calibration During the entire cruise of the past week, the boat speed

instrument (Garmin UDST) seemed to be reading high. The

speed sensor mounted through the hull underwater measures speed of the water

passing by, interprets this as boat speed through the water, and the electronics

display this as boat speed in nautical miles per hour or knots. So we decided to

make a speed calibration run in Chester River between green dayboard

G"1" and the green over red channel junction light Fl (2+1) G 6s 15ft

4M "LC". The measured distance between these beacons is 0.60 NM, and

the bearing in one direction is 096ºT (107ºC) and the reciprocal is 276ºT

(284ºC). This course is at roughly right angles to the current flow. Outbound

leg was from "LC" west to G "1" and Return leg was from G

"1" to "LC". We ran between these beacons at 2400 engine rpm giving us

an indicated boat speed of 7.6 knots for the Outbound leg, and 7.2 knots for the

Return leg. I was at the helm; Johan and Mike marked elapsed time for each run;

JP was lookout for other traffic, and Jerry called out to me to come right or

come left to stay on track to the destination mark as my eyes were paying close

attention to the compass course and the boat speed fluctuations in order to

mentally average the indicated speed. Indicated boat speed through the water Outbound, SIO

= 7.6 knots Indicated boat speed through the water Return, SIR

= 7.2 knots Average Speed Factor, SF = (SFO + SFR)

÷ 2 = (0.85 + 0.86) ÷ 2 = 0.855 In the future, calculate corrected boat speed through the

water, SC = 0.855 x SI (speed through the water indicated

by the Garmin UDST instrument.) This is not GPS speed. And, since distance traveled in a given time period equals

speed divided by time, and since both are based on the same sensor in contact

with the water, the calibration factors for both speed and distance are

numerically equal: Distance Factor, DF = SF = 0.855 In the future, calculate corrected distance traveled

through the water, DC = 0.855 x DI (distance through the

water indicated by instrument.) This is not GPS distance.

Also, we calibrated the steering compass using shadows cast by the Sun for reference as outlined in the Training Plan page D-3. This is the easiest, simplest and most accurate method for calibrating a compass. Bearings to the Sun were measured using a simple sundial built from a 4 inch diameter piece of wood with a 1/8th inch diameter metal rod standing squarely in the middle; dark centerlines were drawn at right angles to each other as shown below. This sundial was placed in the center of a 360º paper compass rose taped to the foredeck of the boat, thus allowing the Sun to cast a shadow of the sundial pin onto the compass rose and thereby provide a direct measurement of the Sun's direction relative to the bow of the boat. In

this photograph, the sun dial appears to be off center from the compass rose,

but this appearance results from the side perspective of the photo... The sun

dial is actually squarely in the center of the compass rose when viewed from

directly above.

A Radar Maneuvering Board paper

chart was used for the 360º compass rose. A dark line was drawn along the 0º

to 180º axis and a second dark line along the 90º to 270º axis. We taped this

compass rose to the foredeck of the boat with 0º toward the bow and 180º

toward the stern and the 0º to 180º axis aligned with the boat fore and aft

centerline. This was then used to measure angles relative to the bow of

the boat. The boat was headed in eight different directions around an

octagonal course. Each boat heading was read directly from the steering compass,

and the shadow cast by the Sun was marked on the compass rose chart shown above.

Time was recorded at the moment of marking the shadow to enable calculation of

the True direction to the Sun as follows:

Date: October 15, 2020 Calibration results are shown in the three tables below.

These results are considerably different than the previous Deviation Table, which may be due to the extensive electrical repairs completed in August after the lightening strike. We will redo this calibration in the future to verify.

As outlined in the

Training Plan, we made entries into the Deck Logbook during the cruise to record

essential information including:

o

Course steered during the

previous hour o

Distance odometer reading o

Wind direction & speed o

Wave direction and height o

Barometer o

Sea water temperature o

Cloud coverage percentage

and type o

Battery voltages o

Bilge water level and

pumpout time o

Initials for completed

boat inspection per checklist o

DR calculations for

distance and course steered Since this advanced

coastal cruise is, among other things, intended as a stepping-stone experience

for sailors planning to make blue water ocean passages, the Training Plan

requires students to plot a Dead Reckoning course similar to what is done

offshore in conjunction with celestial navigation. To accomplish this, Logbook data

starting at noon on October 13, between Elbow of Cross Ledge Range in Delaware Bay and Cape Charles

was reduced and plotted on an NGA #926 Position Plotting Sheet. Starting point

was 39º12.7'N and 075º17.6'W at buoy G "31" Fl G 2.5 seconds in

Cross Ledge Range of Delaware Bay. Following is an

extract from our Deck Log hourly data during the cruise from noon on Oct 13 to

noon on Oct 14. The first four columns are entered by the Helmsman at completion

of each one-hour watch trick; the last column is used for the DR calculations as

follows: ·

Courses will be plotted in

True degrees, so it was necessary to convert the Compass courses to Magnetic and

then to True degrees as shown in the TVMDC tables. Magnetic Variation was taken

from the compass roses on Charts 12304 and 12200, updated to the current year

and rounded to a whole number of degrees. Compass deviation was looked up in the

boat's Deviation Table shown in the Training Plan. · Distances were calculated for each 4-hour period by subtracting one log reading from the log reading four hours later. For example, for the interval from 1200 to 1600, D = 1916 - 1888 = 28 NM, and the corrected distance, DC = 0.85 x 28 = 23.8 NM using the distance correction factor determined recently as described above.

Resulting

DR was then plotted as shown below. It shows good correlation between the DR

results after 24 hours of sailing when we arrived a red buoy R "2N"

off Cape Charles, using only the steering compass and the distance log for the

DR. I generally find good correlation between the DR and actual position if the

Logbook entries and faithfully and consistently made by the crew. I call them my

collection of compensating errors and have seen similar good correlation over

years of sailing offshore. On an ocean passage, this DR plot will then be used

in conjunction with celestial lines of position (LOPs) to carryout an ocean

navigation process using these classical techniques.

Arrival We

arrived back at home port Lankford Bay Marina around 1600 on Thursday, October

15th after completing this 450 mile circumnavigation of the DMVA Peninsula in

four and a half days with one stop along the way. We had some excellent sailing

weather, and prudently avoided the two gales that Mother Nature threw in our way

on Monday and Friday by amending our sailing schedule to suit. An important

principle of advanced coastal sailing, any sailing, is to avoid bad weather if

possible by altering schedules. My crew: Mike, JP, Johan, and Mate Jerry were

wonderful to be with on this really exciting cruise. They were all-in with the

learning experience and served very well as good shipmates with enthusiasm and

good cheer. Fair

Winds! Captain

Tom Tursi |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Web site design by F. Hayden Designs, Inc.